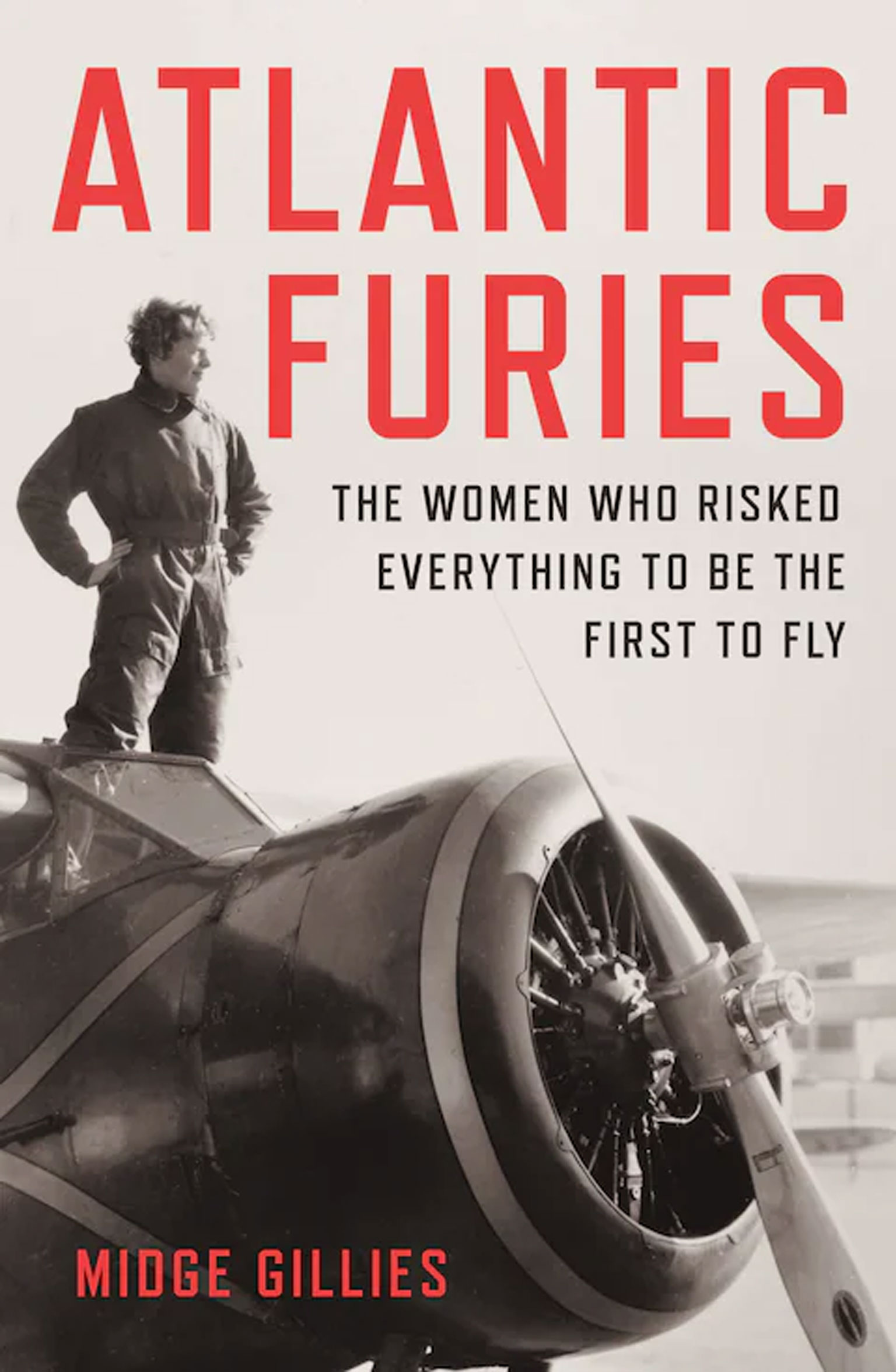

The heroines who raced to conquer the Atlantic (and often died trying)

These daring women ‘risked everything’ to be the first to fly the gruelling, 3,000-mile journey

In May 1927, Charles Lindbergh made the first solo non-stop transatlantic flight. He travelled from New York to Paris, through icy fog and deep fatigue. It took him over 33 hours. Spurred on by Lindbergh’s feat, several women in Britain and America wanted to prove that it wasn’t just men who could endure that gruelling, lonely, 3,000-mile journey: whether it was as pilots or passengers, they could do it too.

Frances Grayson was one such pioneer. She was 35, with a failed marriage and several abortive careers behind her. Two days before Christmas 1927, amid disastrous weather warnings, she and a crew of three men – pilot, engineer, radio operator – took off from Long Island. Aiming for a first stop on Newfoundland, the team flew north-east over Cape Cod and headed out to sea. They were never seen again.

As the social historian Midge Gillies writes in Atlantic Furies, her detailed and enjoyable survey of “the women who risked everything to be the first to fly”, Grayson’s “final moments must have been horrific… [and] plunging into the icy sea beyond terrifying.” The aviATLANTIC atrix had left a statement to be read in the event of her death. Her motive appeared to have been merely the determination that her life amount to something – “or I become a little nobody”.

Grayson’s loss did little to deter other women. For, as Gillies brilliantly conveys, flying long-distance – and doing it, eventually, solo – wasn’t simply about the thrills and risks involved in conquering the elements. For women in the 1920s, transatlantic flight was also about rising above their situation in life, avoiding boredom by seeking adventure, and, just as the suffragettes were doing in the British political sphere, proving the need for equality.

Ladies who launch: pioneering aviators Frances Grayson, Elsie Mackay and Mabel Boll

Such flights were arduous. They involved long hours of concentration, often in freezing and noisy conditions. The smallest lapse could prove fatal. The fuel needed to cross an ocean was so heavy it threatened to destabilise the plane. Given the length of the journey and lack of places to stop, coffee was welcomed, though since it was almost impossible for women to urinate during a flight, Gillies speculates that they probably resorted to adult nappies.

It wasn’t easy for female aviators to find teachers, or husbands who would allow their spouses to fly in any role. If a woman was able to gain experience, it was probably by undertaking short flights that involved the aid of landmarks, not flying solely by instruments –

which the Atlantic crossing, over so much featureless water, would demand. It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, that the “Furies” of Gillies’s title – six women who were determined to cross the ocean in 1927 and 1928 – accumulated at least 15 marriages between them, and struggled to be taken seriously in what Gillies calls the “testosteronesoaked world of flying”.

Many such would-be pilots didn’t have financial resources of their own; they needed backers to pay for the machinery and crew. Lady Anne Savile was a wealthy widow and flying enthusiast; when she attempted the flight (as a passenger) in August 1927, neither she nor her two male crew made it. The Hon Elsie Mackay, a former actress and jockey, was 35 in March 1928 when she attempted the east-west crossing, but she did so in secret, hoping this would prevent her family from trying to stop her. Her plane, Endeavour, likewise vanished.

One pivotal character in Gillies’s book is Amy Guest, a wealthy American and mother-of-three. She’d grown up as a tomboy with an adventurous spirit and hoped to become the first female transatlantic pilot herself, but she was talked out of that in favour of supporting another amateur: Amelia Earhart. Guest duly ploughed millions into supporting Earhart’s quest. By early 1928, six months after Grayson’s disaster, Earhart was making serious plans and vying for the achievement with Mabel Boll, a bartender’s daughter who’d married a wealthy businessman and was renowned for wearing as many as 33 diamond bracelets on one arm.

On June 3 1928, in Boston, Earhart climbed aboard her Fokker F.VIIb Tri-Motor (named Friendship). Her pilot was Bill Stultz; the co-pilot was Slim Gordon. Earhart wedged herself into a cramped seat behind the pair, next to some additional fuel tanks, and they took off. After stopping in Newfoundland, where they spent two weeks grounded by bad weather – Boll and her crew were already on the island, stuck in the same position – they took their chance, and lifted off again, heading east. After 20 hours and 40 minutes, they safely landed in Burry Port, south Wales, making Earhart the first woman to fly across the Atlantic.

The last leg of Friendship’s journey took it from Burry Port to Southampton, where Earhart was mobbed as if she had been the one at the controls. She disavowed all the praise, calling herself “baggage”; but she was a budding pilot herself, and having now witnessed what was involved, she couldn’t rest until she made the flight solo. In 1931 she married the publisher George Putnam, a decade older than her, setting him the condition that she be free to pursue her career. He was supportive, seeing the publishing opportunities in Earhart’s feats. In May 1932, five years after Lindbergh’s historic flight, she succeeded.

Then, on 1 June 1937, Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, attempted to fly around the world. After travelling over the continental US, down through the Caribbean and South America, to Africa and across most of Asia, they reached New Guinea on June 29. They took off again on July 2, in deteriorating weather, after which Earhart was never seen again. She was declared legally dead in 1939; theories about her death continue to this day, not least on account of the discovery of bones and some items of clothing on the volcanic atoll of Nikumaroro.

Even if Earhart failed in one sense, she succeeded in another. Her mysterious, unsolved death has fixed her place in the public imagination as a woman who permanently changed the perceptions of what women could achieve – and not just in flying. As Gillies’s book makes abundantly clear, the “Atlantic Furies” had to fight relentlessly; their goal as to have what women could do, if given a chance. And yet, today, there are still relatively low numbers of women in the aviation industries: fewer than eight percent of private pilots are women; Earhart and co were trailblazers – but almost 90 years on, women are a long way from dominating the skies.